Khor Rori

A couple of minutes’ walk below the ruins of Sumhuram lies the tranquil Khor Rori, the most attractive of the various khors (creeks) which line the coastline around Salalah. A neat pair of symmetrical headlands flanks the mouth of the khor, which is separated from the sea by a low sand bank. As a result, the waters inside the creek (fed by Wadi Darbat) are freshwater, and full of fish, which in turn attract a fine selection of aquatic birds, while camels can usually be seen browsing the surrounding greenery. It’s a wonderfully peaceful spot – so quiet that you can actually hear the splashes of fish in the water.

Mirbat

A couple of kilometres beyond Bin Ali’s Mausoleum lies personable MIRBAT, one of the Dhofar’s most interesting smaller towns, and another in the chain of erstwhile frankincense ports which line the coast. Two miniature statues of prancing horses atop columns flank the entrance to the town – a whimsical memorial to its history as an important breeding centre for Arabian steeds. A short distance further you’ll see the town’s small fort just off the road on your right, standing proudly above the waves, with fine views of the coast, beach and mountains beyond. The building is currently fenced off for renovations, though you can make out the unusual hexagonal tower at one corner and neat shuttered windows in square stone frames.

Immediately below the fort lies the old harbour, a picture-perfect little sandy cove, dotted with boats and enclosed by a low rocky headland at the far end. Walking across the sand brings you to Mirbat’s old town, a wonderful area of old Dhofari-style houses. Most are simple one- or two-storey cubist boxes, painted in faded oranges, blues and whites, their minimalist outlines enlivened with distinctive wooden-shuttered windows. There’s a particularly grand trio of large three-storey structures (one ruined) next to the main road, with diminutive towers and battlemented roofs, like miniature forts, strikingly similar to the domestic architecture of nearby Yemen. The one right next to the main road is particularly fine, with a couple of intricately carved wooden shutters, spiky battlements and a picture of a dhow etched into the plasterwork at the top of the small corner turret at the rear. Beyond here lies Mirbat’s prettier-than-average main street, with shops painted in cheery pastel pinks and oranges and decorated with big green shutters.

The Battle of Mirbat

Mirbat Fort was the scene of perhaps the most important single conflict of the entire Dhofar Rebellion, and what is also frequently claimed to be the finest moment in the history of the British SAS. The Battle of Mirbat began early in the morning of July 19, 1972, when around 300 heavily armed fighters of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Oman (PFLOAG) attacked the town’s small garrison, based in the fort and surrounding buildings, guarded by just nine SAS soldiers and thirty-odd Omani troops, all under the command of Captain Mike Kealy, aged just 23.

The aim of the rebels was simple: to disrupt Sultan Qaboos’s new policy of rapprochement; to demonstrate the weakness of the government’s control even over towns close to Salalah itself; and to execute as many local government supporters as they could find in Mirbat itself once they had overwhelmed the garrison. The fact that this major political setback, and the potential murder of innocent civilians, was averted is mainly down to the skill and courage of the soldiers defending the garrison. The bravery of Fijian sergeant Talaiasi Labalaba in particular – who somehow succeeded in holding large numbers of PFLOAG fighters at bay by single-handedly operating an old World War II 25-pound artillery piece (a job normally requiring three men) despite severe injuries – has become the stuff of military legend. After hours of bitter fighting, but with the loss of just two men (including Labalaba), air support and SAS reinforcements arrived from Salalah, after which the rebel forces were driven back into the hills.

The battle was a major setback for the rebels, who lost perhaps as many as 200 fighters. Their failure to seize Mirbat, even with vastly superior forces, also boosted the morale and standing of government forces, and the peace effort in general. Sadly, the UK government’s anxiety to keep the fact that British fighters were involved in Dhofar secret meant that the battle received little attention overseas, and those involved largely failed to receive the recognition many people feel they deserve. Campaigns to have Sergeant Labalaba awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross have so far come to nothing.

Sumhuram

Back on the main coastal highway past the Wadi Darbat turning lie the absorbing remains of the old city of SUMHURAM, now protected as the Sumhuram Archeological Park. Along with the nearby city of Zafar, this was formerly one of the major ports of Southern Arabia and an important conduit for the international frankincense trade network. There are two wildly conflicting theories about the origins of the city based on the inscription found at the gateway. According to the official handbook to the site, the city was founded in the third century BC by a local ruler named Sumhuram (or Samaram); according to Nicholas Clapp in The Road to Ubar, the inscription states that the city was founded by King Il’ad Yalut I of the Hadhramaut (in what is now Yemen) “not earlier than 20 AD”. The city survived for 500 (or possibly 800) years before being gradually abandoned in the fifth century AD, perhaps due to the formation of the sand bar across the mouth of Khor Rori, which closed the creek to shipping.

To reach Sumhuram, take the signed turning on the right off the main coastal highway 750m past the turning to Tawi Attair (and 8km beyond Taqah); follow this tarmac road for about 2km to reach the entrance to the site. There are a couple of misleadingly placed brown signs in the vicinity of Taqah which appear to be pointing you onto dirt tracks – ignore them. There’s a useful printed guide to Sumhuram available at the ticket office for 2 OR, while informative signs dotted around the site provide interesting historical and archeological background snippets.

The site

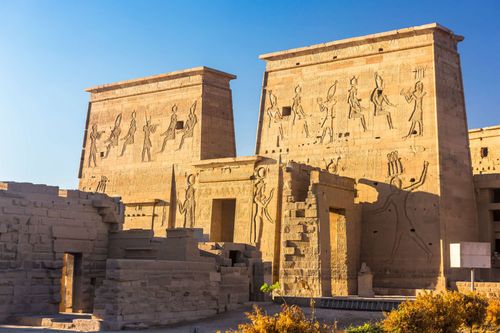

The ruins of Sumhuram are far less extensive than those at Al Baleed, but have been much more thoroughly excavated and restored, while the lovely natural setting between coast and hills adds to the appeal. The ruins sit atop a small hill above the tranquil waters of Khor Rori: a neat rectangle of off-white buildings enclosed by impregnable walls made out of huge, roughly hewn slabs of limestone; the walls are more than 3m thick in places, and perhaps originally stood up to 10m high. Entrance to the city is via the remains of a small gateway, inside of which you’ll find two beautifully preserved inscriptions commemorating the foundation of the city, carved in the ancient South Arabic (or “Old Yemeni”) musnad alphabet.

Inside, the town is divided into residential, commercial and religious areas, with the slight remains of a maze of small buildings packed densely together. These were originally at least two storeys tall (as the remains of stone stairways attest), although not much now survives of most beyond the bases of their ground-floor walls. The city’s most impressive surviving structure is the Temple of Sin (the Mesopotamian moon god), built up against the northwest city wall – look out for the finely carved limestone basin in the ritual ablution room within. Nearby, the so-called Monumental Building is thought to have housed the city’s main freshwater reservoir and well. At the rear of the complex stands the small Sea Gate, from which goods were transported down to boats on the water below.

_listing_1481212452382.jpeg)