Brief history of Tangier

Tingis is Amazigh (Berber) for a marsh, revealing the site’s Berber origins, though it was colonized around the seventh century BC by the Phoenicians, a seafaring people from what is now Lebanon. In 42 AD, the Romans made Tingis the capital of their newly created province of Mauretania Tingitania (roughly the north of modern Morocco). In 429 AD, with the collapse of the Roman Empire’s western half, Tangier was taken by the Vandals, after which point things become a bit hazy. It seems to have been regained a century or so later by the Roman Empire’s resurgent eastern half in the form of the Byzantines, before falling to Spain’s rulers, the Visigoths, in the early seventh century.

Andalusian and European Influence

In 707, Tangier was taken by the Arabs, who used it as a base for their invasion of the Iberian Peninsula four years later. However, with the Christian reconquest of Spain and Portugal from the eleventh to fifteenth centuries, Tangier was itself vulnerable to attack from across the Straits, and eventually fell to the Portuguese in 1471. In 1661, they gave it to the British (along with Bombay) as part of Princess Catherine of Braganza’s dowry on her wedding to Charles II. Tangier’s Portuguese residents, accusing British troops of looting and rape, abandoned the town, but new settlers arrived, many of them Jewish refugees from Spain, and Britain granted the city a charter guaranteeing freedom of religion, trade and immigration. The British also introduced tea, now Morocco’s national drink. Under virtually constant siege, however, they found Tangier an expensive and unrewarding possession. Moulay Ismail laid siege to the city in 1678, and in 1680, England’s parliament refused any further funding to defend it. Four years later, unable to withstand the siege any longer, the British abandoned Tangier. The city then remained in Moroccan hands until the twentieth century, growing in importance as a port – one of its exports, mandarins, even took their name from the city, being known in Europe as tangerines.

Tangier’s strategic position made it a coveted prize for all the colonial powers at the end of the nineteenth century. European representatives started insinuating themselves into the administration of the city, taking control of vital parts of the infrastructure, and when France and Spain decided to carve up Morocco between them, Britain insisted that Tangier should become an International Zone, with all Western powers having an equal measure of control. This was agreed as early as 1905, and finalized by treaty in 1923. An area of 380 square kilometres, with some 150,000 inhabitants, the International Zone was governed by a Legislative Assembly headed by a representative of the sultan called the Mendoub. While legislative power rested with the assembly – consisting of 27 members of whom 18 were European – the real power was held by a French governor.

Morocco takes control

At the International Zone’s peak in the early 1950s, Tangier’s foreign communities numbered sixty thousand – then nearly half the population. As for the other half, pro-independence demonstrations in 1952 and 1953 made it abundantly clear that most Tanjawis (natives of Tangier) wanted to be part of a united, independent Morocco. When they gained their wish in 1956, Tangier lost its special status, and almost overnight, the finance and banking businesses shifted their operations to Spain and Switzerland. The expatriate communities dwindled too as the new national government imposed bureaucratic controls and instituted a “clean-up” of the city. Brothels – previously numbering almost a hundred – were banned, and in the early 1960s “The Great Scandal” erupted, sparked by a number of paedophile convictions and escalating into a wholesale closure of the once outrageous gay bars.

Tangier today

After a period of significant decline, the early 2000s saw Tangier reborn as one of the country’s premier beach holiday resorts as both the Moroccan government and foreign investors directed more interest (and more funds) towards the city and its future. Marketed mainly towards the domestic market as well as day-tripping Spaniards, Tangier’s regeneration shows no sign of fading. Construction work began in 2011 on a five-year project that will eventually see the old port transformed into a glitzy residential marina complete with designer shops and a five-star hotel.

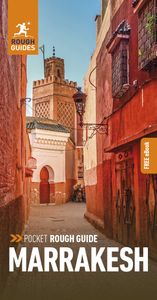

Tangier Medina

The layout within Tangier’s Medina, like most throughout Morocco, was never planned in advance. As the need arose, a labyrinth of streets and small squares emerged that eventually became the various quarters there today.

Looking at it today, the Petit Socco, or Zoco Chico (Little Market), seems too small ever to have served such a purpose, though up until the nineteenth century the square was almost twice its present size, and it was only at the beginning of the twentieth century that the hotels and cafés were built. Up until the 1930s, when the focus moved to the Ville Nouvelle, this was the true heart of Tangier, and a broad mix of people – Christians, Jews and Muslims, Moroccans, Europeans and Americans – would gather here daily.

In the heyday of the “International City”, with easily exploited Arab and Spanish sexuality a major attraction, it was in the alleys behind the Socco that the straight and gay brothels were concentrated. William Burroughs used to hang out around the square: “I get averages of ten very attractive propositions a day”, he wrote to Allen Ginsberg. The Socco cafés lost much of their appeal at independence, when the sale of alcohol was banned in the Medina, but they remain diverting places to sit around, people-watch, talk and get some measure of the Medina.

The Ville Nouvelle

Sprawling westwards and southwards from the ancient Medina is the European-built Ville Nouvelle. Much of its architecture and layout, especially immediately outside the Medina, is of Spanish origin, reflecting the influence of the city’s large Spanish population during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The Grand Socco is the obvious place to start a ramble around the town. Its name, like so many in Tangier, is a French–Spanish hybrid, proclaiming its origins as the main market square. The markets have since long gone, but the square remains a meeting place and its cafés make good spots to soak up the city’s life. The Grand Socco’s official but little-used name, Place du 9 Avril 1947, commemorates the visit of Sultan Mohammed V to the city on that date – an occasion when, for the first time and at some personal risk, he identified himself with the struggle for Moroccan independence.

A memorial to this event (in Arabic) is to be found amid the Mendoubia gardens, flanking the square, which enclose the former offices of the Mendoub – the sultan’s representative during the international years – and now home to the local Chamber of Commerce. Here there’s also a spectacular banyan tree, said to be over 800 years old. Essentially now an open grassed area, the gardens are popular with local families who enjoy the small playground.

Malcolm Forbes: Tangier’s last tycoon

The American publishing tycoon Malcolm Forbes bought the Dar el Mendoub, Rue Mohammed Tazi, in 1970. His reason, ostensibly at least, was the acquisition of a base for launching and publishing an Arab-language version of Forbes Magazine – the “millionaires’ journal”. For the next two decades, until his death in 1990, he was a regular visitor to the city, and it was at Dar el Mendoub that he decided to host his last great extravagance, his seventieth birthday party, in 1989.

This was the grandest social occasion Tangier had seen since the days of Woolworths heiress Barbara Hutton, whose scale and spectacle Forbes presumably intended to emulate and exceed. Spending an estimated $2.5m, he brought in his friend Elizabeth Taylor as co-host and chartered a 747, a DC-8 and Concorde to fly in eight hundred of the world’s rich and famous from New York and London. The party entertainment was on an equally imperial scale, including six hundred drummers, acrobats and dancers, and a fantasia – a cavalry charge which ends with the firing of muskets into the air – by three hundred Berber horsemen.

Forbes’s party was a mixed public relations exercise, with even the gossip press feeling qualms about such a display of American affluence in a country like Morocco. However, Forbes most likely considered the party a success, for his guests included not just the celebrity rich – Gianni Agnelli, Robert Maxwell, Barbara Walters, Henry Kissinger – but half a dozen US state governors and the chief executives or presidents of scores of multinational corporations likely to advertise in his magazine. And, of course, it was tax deductible.

After Forbes’s death, Dar el Mendoub passed into the hands of the state and was used to house personal guests of King Hassan II, before being converted into a museum. It has now reverted back to being a VIP residence for royal and state guests.